|

In the late 1870s, Richard Doherty's Irish ancestors gave up everything

they knew to make a new home with other immigrants in a place called

Stuart

,

Iowa

.

In this new place, no one was going to tell them they couldn't own land

just because they weren't Protestant.

No one was going to make it illegal to celebrate

Mass.

For these Irish immigrants and their children, there would be no more

killing, no more death, committed under the name of God.

"They weren't a people who had a lot of money when they came

here," says Doherty. But

Iowa

was a fresh start, and with the railroad coming through Stuart, they had

reason to believe that good times were ahead.

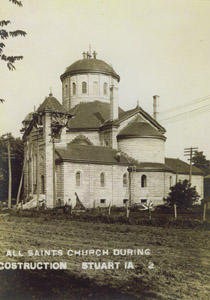

After several years, the young community embarked on a particularly

ambitious project: construction of a massive, Byzantine-style church,

now believed to be patterned after St. Mark's in

Venice

.

Stonecutters from

Scotland

were brought in to hand-cut the limestone exterior walls. The Italian

Baroque interior was capped with a copper dome reaching 90 feet into the

air, hovering over a sanctuary seating 600.

Ornamentation could be found everywhere in that church, even in the

Corinthian column detailing on steel support beams.

The altars were Italian marble.

The stained-glass windows were imported from

Munich

.

Four frescoes were hand-painted on the high arched ceilings.

All Saints Catholic Church was consecrated in 1910, becoming one

of the few examples of Byzantine architecture in the American Midwest.

Both Catholics and non-Catholics in the community had joined together to

donate their money and make it happen.

Meanwhile, the town's fortunes weren't panning out exactly as expected:

The railroad yards suddenly shifted to

West Des Moines

, making Stuart less of a commercial center than it might have been

otherwise. Still, the church thrived, regularly drawing parishioners

from Earlham, Dexter, Menlo and Redfield.

The old church rested, literally, on the labor of its immigrants:

Farmers living north of town used horses and wagons to haul its

underground foundation stones into place.

One of those farmers doing the hauling had been Doherty's

great-grandfather. So it's perhaps historically appropriate that Doherty

serves as president of Project Restore, the nonprofit, non-sectarian

group trying to restore All Saints after the 1995 arson that left behind

just a shadow of the church's former splendor.

The foundation's stated mission: to promote religious tolerance, and to

preserve cultural heritage.

A

war within

The 1995 fire had been set by a

Des Moines

man consumed with hatred over the Catholic Church's stands on

homosexuality, abortion and other issues.

He targeted the Stuart church specifically because it was so beautiful

and he wanted to strike out at the "heart and soul of Catholic

Iowa."

As Doherty and other Stuart residents stood watching their beloved

church burn, many of them vowed on the spot that it would be rebuilt.

But ironically, the people trying to bring the old church back to life

found themselves at odds with people from their own diocese and their

own parish council - people who thought it would be more sensible to

take the $3.9 million insurance settlement, build a more modest $3

million church to replace it, and have cash left over.

The Des Moines Diocese was getting ready to bulldoze the remains of the

old church when long-time church member John Slayton climbed on top of

it as a media stunt. It worked: Reporters showed up, central Iowans were

talking, and the church leaders decided not to bulldoze the place, after

all.

"It cost me two days in jail, but it was well worth it," says

Slayton, who has remained active in Project Restore's renovation

efforts.

While some argued that restoring the old church was just financially

impractical, the preservationists knew how to work with the media and

focus public attention on the diocese's actions. After five years in the

media spotlight, Doherty says, "I think they were ready to sell it

to us."

The preservationists are now restoring the old church as quickly as the

donation money comes in. Doherty took early retirement partly so he

could devote more time to All Saints.

"It means a lot to me," Doherty says. "Even in the ruins,

it's still a beautiful building."

For the community, losing this church was as gut-wrenching as losing a

family member, he says. "It's all the weddings, the funerals

they've been to, the first communions. It was the history of their

life."

Slayton remembers the feelings of awe that he had as a little boy when

attending services at the glorious old church. It was a part of his

family life: "My grandma went there, and all my relation, and my

mom was married there. Both my kids were baptized there."

However, Slayton says he feels so betrayed by the church leaders who

didn't want to save the old building that he's no longer a practicing

Catholic.

"I'm not going to be around that bunch," he says.

The arson "could have brought us closer together than anything. But

it actually split the town and the church," Slayton says.

"It's really too bad. We shouldn't have ever let the arson get the

best of us, and we did."

The diocese opened a new, modern church in Stuart in 1999.

Ann Shea, age 94, spent 70 years singing in the choir at All Saints. For

70 years, she fixed the flowers every week on its three altars. She's

one of the many who believe that the Catholic leadership should have

renovated the old structure "instead of building this other barn

out here, as we call it."

So far, more than 3,000 people have donated money, time and technical

expertise to bringing the old church back to life.

Half of those donors, Doherty figures, aren't even Catholic.

Holy ground

So far, Doherty estimates, Project Restore has

spent somewhere around $300,000 on repairs, mostly on the west end of

the church. The group has created a chapel area, which it's rented out

for a handful of weddings and a business conference.

The fees help toward renovations and expenses, but more than that,

Doherty says the rentals are a way to bring life back into the old

church.

The brick and stone walls are still sound. But the arson burned the

sanctuary floor as well as the ceiling above it, forming a cavernous

grotto that's open to the sky.

Long

ago, Project Restore hauled away the debris and salvaged whatever

religious objects might be restored later, such as the Stations of the

Cross statues, charred black and split open in places, revealing the

horse hair and straw that the old plaster had been formed around.

Hawks and a squirrel now take refuge where people used to sing and pray.

The empty walls block the north wind. Two timber owls spend the winter

there, and last summer, a pair of peregrine falcons hatched a brood in a

place that visitors from various religious traditions are still

describing as sacred ground.

Doherty says, "You can stand in the basement down there, and you

feel it's a sacred place."

Many of the visitors to the site say the church shell reminds them of

post-war

Europe

. "They'll say it looks like a lot of the World War II buildings,

after the bombing," Doherty says.

Recently, newly immigrated Orthodox Christian Serbs began holding

services in the restored chapel.

Near the chapel, down a hallway and through a window, Serbs can see the

vacant space where the old sanctuary had been. With the Byzantine

architecture, All Saints reminds them exactly of what they just left: It

reminds them of their churches that have been burned, their cemeteries

that have been destroyed, all because people of different religions have

been unable to get along.

This Saturday, the Serbs are holding a service at All Saints with

Metropolitan Christopher, Primate of the Serbian Orthodox Church in

North America

.

As far as Doherty can tell, he's the highest-ranking church official

who's ever come to

Stuart

,

Iowa

.

As soon as the Serbs saw the old building, they were eager to help

rebuild it.

Doherty figures that's not so different from the attitude among the

first immigrants who moved to Stuart.

"It's just a circle," he says.

|